"Diversity Rounds" Reveals Tapestry of Similarities & Differences

Unfortunately, participants in a regular five-day Critical Friends Group training don't get to experience every protocol in the National School Reform Faculty (NSRF) collection. That collection includes 322 protocols, activities, or modifications that all can be used differently to help your team achieve its goals. One of these protocols is called "Diversity Rounds," and until I had a special request from a group to use it this summer, I had never tried it before. Now that I've tried it, I try to work it into every training!

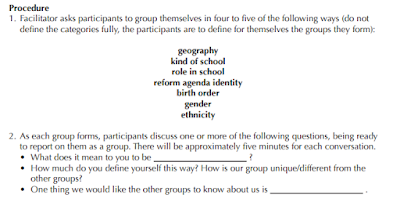

Diversity Rounds requires the facilitator to identify a category where diversity exists. It then allows participants to decide how to best "subdivide" that category into two to four subcategories. The first two steps of the procedure are printed as follows:

With the group I was working with, we first used "Birth Order" as a category and after a small hesitation, someone in the room took charge. She suggested the group break subdivide into a group of those who were "first born," a group of those who were "middle children," and a group of those who were the "babies" of their families. As you might have expected, we had some people who didn't fit any of these groups. People who were the "only child" and people who were the "fourth of five children" didn't have a place. However, these people joined a group anyway and later reported that they felt out-of-place as they tried to respond to the three questions with their group. Though a person who is an only child may also be a "first born," he or she may have had a very different experience than a first born of a large family.

This out-of-place awkwardness, however, is a critical piece of this protocol. It is designed to help people understand the challenges we face when we are a minority in a situation. While others were reminiscing about their common pasts as first-borns - for instance - the out-of-place participants experienced first-hand the challenges that come with mixing into a pre-existing group of people.

In the next "round," I asked participants to group themselves according to "religion." Again, someone in the room took charge and they broke into three groups based on specific religions. As you might expect, there were again two individuals (in a group of 12) who did not have a group to go to. One woman believed in God and considered herself very morally sound, but she didn't go to church regularly. Another woman said she was more of an agnostic. Both of these women felt out-of-place and a little judged (I would learn later) because they considered themselves good people, but they felt like their lack of organized religion made them look less morally-committed to the group.

Finally, Round 3 asked the group to subdivide based on "ethnicity." The group chose to subdivide into two different types of European ethnicities and made a third group based on African ethnicities. This may have been the most informative round yet. First, the group noted that one woman in the group could not fit into any of these three ethnicities. Her family had been American slaves, she said, and they no longer traced any of their lineage back to Africa because they didn't know where they may have come from. As a result, she felt out of place, but she went to the "African" group. Importantly, the other two women in this group felt that their placement was perfect. Not only because they could trace their lineage back to Africa, but they had actually lived in the country at some point.

Once this point was made, the other participants also recognized their lack of connection to either of the European "ethnicities" they had placed themselves within. Though we were at a school on the East Coast, many of these participants had some from the Midwest, the Northeast, or Florida. After the group had completed this round, they indicated that they felt it would have been better if they had a chance to divide according to the places they had spent most of their lives living.

This protocol taught my group and me multiple things:

Diversity Rounds requires the facilitator to identify a category where diversity exists. It then allows participants to decide how to best "subdivide" that category into two to four subcategories. The first two steps of the procedure are printed as follows:

With the group I was working with, we first used "Birth Order" as a category and after a small hesitation, someone in the room took charge. She suggested the group break subdivide into a group of those who were "first born," a group of those who were "middle children," and a group of those who were the "babies" of their families. As you might have expected, we had some people who didn't fit any of these groups. People who were the "only child" and people who were the "fourth of five children" didn't have a place. However, these people joined a group anyway and later reported that they felt out-of-place as they tried to respond to the three questions with their group. Though a person who is an only child may also be a "first born," he or she may have had a very different experience than a first born of a large family.

This out-of-place awkwardness, however, is a critical piece of this protocol. It is designed to help people understand the challenges we face when we are a minority in a situation. While others were reminiscing about their common pasts as first-borns - for instance - the out-of-place participants experienced first-hand the challenges that come with mixing into a pre-existing group of people.

In the next "round," I asked participants to group themselves according to "religion." Again, someone in the room took charge and they broke into three groups based on specific religions. As you might expect, there were again two individuals (in a group of 12) who did not have a group to go to. One woman believed in God and considered herself very morally sound, but she didn't go to church regularly. Another woman said she was more of an agnostic. Both of these women felt out-of-place and a little judged (I would learn later) because they considered themselves good people, but they felt like their lack of organized religion made them look less morally-committed to the group.

Finally, Round 3 asked the group to subdivide based on "ethnicity." The group chose to subdivide into two different types of European ethnicities and made a third group based on African ethnicities. This may have been the most informative round yet. First, the group noted that one woman in the group could not fit into any of these three ethnicities. Her family had been American slaves, she said, and they no longer traced any of their lineage back to Africa because they didn't know where they may have come from. As a result, she felt out of place, but she went to the "African" group. Importantly, the other two women in this group felt that their placement was perfect. Not only because they could trace their lineage back to Africa, but they had actually lived in the country at some point.

Once this point was made, the other participants also recognized their lack of connection to either of the European "ethnicities" they had placed themselves within. Though we were at a school on the East Coast, many of these participants had some from the Midwest, the Northeast, or Florida. After the group had completed this round, they indicated that they felt it would have been better if they had a chance to divide according to the places they had spent most of their lives living.

This protocol taught my group and me multiple things:

- It is important to always be on the lookout for those people who might feel "out-of-place" due to a difference, even one as subtle as birth order. Helping these people to connect with similarities can be important to the culture of the places where we work.

- While we may look the same or look different, there are going to be similarities that connect us. It was exciting seeing the participants who had lived in the Midwest rally around what pieces of that experience had shaped them to be the people they were today. Those who had lived in other parts of the country had a similar experience.

Helping others, especially young people, to understand the many different types of diversity can be a challenge. This protocol, however, opened eyes and made it easier for the adults I worked with to understand their role in celebrating diversity and finding those common threads that bind us.

Comments

Post a Comment